A shepherd’s life in the sagebrush sea

The practice of transhumance involves man and beast living together on the land, moving together with the seasons, responding to natural conditions. It involves becoming a part of nature.

The land outside my door is a land of contrasts. Today it is a place of supple beauty, the quiet of dawn punctuated only by the soft call of a golden eagle on her rock perch half a mile away, and the quork, quork of a murder of ravens as they fly over, inspecting my outpost. Yet while the sunlight spreads its golden rays over my nestled camp, I look up to see a winter storm raging over the granite peaks in the distance, the highline buried in a startling ribbon of white. I’m only an hour from our home ranch, but it’s as though I’m on the other side of the world. The landscape resembles the steppes of Mongolia. In fact, today it feels like Mongolia. I know this, having been drawn to the Mongolian steppe, and feeling at home in that amber Asian light.

Like the Mongolian nomads whose lives are tied to the herds they tend, I am here to watch over my sheep. I am alone in camp, with one herding dog, three guardian dogs, and several hundred pregnant ewes. The sheep are slated to begin giving birth in less than a week, and it’s my responsibility to shepherd them, to keep them safe.

There are no houses within view, no lights at night to mar the pristine darkness other than that of the moon, the stars, and my flickering candle.

We’re new to the neighborhood, having trucked the sheep in yesterday, the first of May. We’ve received many shy visitors in the hours since our arrival, most in the form of curious avians, fluttering, flickering, hovering above, checking out the newcomers. Yesterday, despite the gusting winds of late afternoon, we were greeted by the smallest of the falcons, an American kestrel. A fluttering of wings above the bedded sheep, the kestrel zigzagged just out of reach. Small groups of pronghorn antelope raced in to see the new ungulates on their range, only to come to an abrupt halt, snorting their displeasure at our trespass. The pronghorn gradually calmed, pointing their dramatically marked faces to the ground, nibbling the fresh spring growth, succumbing to an acceptance of shared range.

I take comfort in the fact that, forty miles to the south, sheepherders from Nepal tend to other herds grazing this sagebrush range. They are my comrades, kindred spirits. They may have left extended families — their wives, small children, aunts, uncles, cousins, parents, and grandparents — back home in Nepal; they may have once been mercenaries fighting for whoever could pay the most; they may currently be small-businesspeople working in a global climate. No matter their background, this nomadic shepherd life drew them here.

We each have our own stories. This is mine, a season with the sheep.

Note from Cat: Your support for Range Writing is appreciated. If you aren’t already a subscriber, please consider subscribing now. It’s free, and the latest posts will be delivered straight to your inbox weekly.

The wind howled through part of our first night on the range, but when it calmed, I looked out from my warm sleeping bag to discover a bright waning moon lighting up the landscape. Coyotes were howling and yowling in the badlands and clay buttes to the southeast, and my livestock guardian dogs were returning the barrage of sound. I would find sleep difficult in silence, but the low, full-throated boom of a large dog is akin to rocking my cradle.

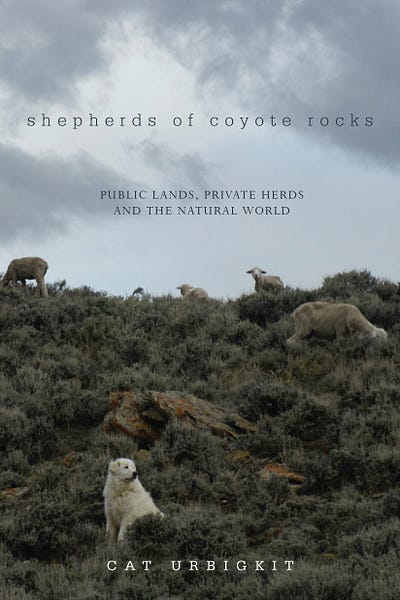

At dawn I rose to check the sheep, which were contentedly moving off their bedding ground, tasting the morning’s frosty morsels, and the livestock guardian dogs began to appear around camp. First Rena, the ambassador of all guardians, came in with enthusiasm, apparently pleased to learn that I had endured the night. Next came the young stud dog, our Russian comrade Rant, limping up from the hills below, stiff and sore, a battle-weary warrior. Luv’s Girl, the oldest and wisest, mother of Rena, trotted in hungry, arising from her bed amid the sheep. Each received fresh water and food along with my adoration. The dogs are tired this morning, and I can only hope that the coyotes are feeling the same way.

Jim called my cell phone (I have cell service only atop the highest hills of this remote rangeland), reporting that the weather would be blustery for the next two days, with a good probability of rain or snow on the third day. Since the morning was fairly calm, I decided after breakfast to take the sheep to the only water hole in the pasture, before the winds began again. The herd had been quenching its thirst on snowdrifts remaining in a few gullies and draws, and with the morning frost on their grazing range. Rena and Abe, my herding dog and constant companion, came along, helping me move the herd to water. The sheep are naturally wary about walking into tall brush and always pause on hills to scope out the scene below before proceeding. Rena took the lead, scouting out ahead of the herd as Abe and I directed from behind. In her position up front, Rena flushed a few sage grouse and chased off the ravens that swooped low overhead.

We arrived at the small impoundment only to find a layer of ice on the surface. While Rena and I got busy busting ice along the edge, the herd proceeded forward, not the slightest bit interested in our efforts. Apparently the morning frost provided all the moisture the animals needed, but at least they would know where to find water later on.

We hurried to catch up, as the sheep grazed atop a mound I had dubbed Coyote Rocks, where golden eagles, sly coyotes, and elusive desert cottontails live a secretive existence. Abe, Rena, and I spent the next hour climbing around, inspecting all the nooks, caves, nests, and dens. The multicolored lichen blanketing the rocks is abundant, as are the whitewash stains left by raptors on their most-frequented perches. The wind resumed its howling while we were thus engaged, with the sheep grazing away from us down below. We made it back to camp just as the clouds moved over us, casting the landscape in shadow, accompanied by gusting cold winds.

The rangeland we inhabit is in the Big Sandy region of western Wyoming, part of the Upper Green River basin. The basin encompasses hundreds of square miles of land, ranging from the high-elevation granite Wind River Mountains, to boulder-strewn foothills, sagebrush steppe, and semiarid desert. The Green River emerges from the Wind River Mountains and flows south through the basin to Wyoming’s border with Utah and Colorado. Farther south, the river merges with the Colorado River, which traverses the western American states to its end in Mexico.

Although there are small towns and ranches in this basin, wildlife and livestock vastly outnumber people. It is a part of the West sometimes called the Empty Interior — thousands of miles of arid and semiarid landscapes that were never fully settled for permanent residency, but traditionally used by drovers for seasonal livestock grazing.

Deemed undesirable for settlement, these areas were declared public lands, to be managed by federal authorities, with grazing as their primary use.

Grazing privileges are parceled out under a federal permitting system, with set durations and conditions for use. A federal grazing allotment can be a series of pastures ranging in size from a few acres to dozens of square miles. Some allotments are species-specific (intended only for sheep or cattle, for example), while others can be grazed by various herds. Some allotments provide for grazing by one ranch, while others, called common allotments, allow numerous ranches (often in the form of grazing associations) to combine their livestock and graze their animals together.

The rangeland my sheep are inhabiting this year encompasses nearly thirty square miles. The smallest pasture is only a few square miles, and fenced on all sides. The other pastures are up to seventeen square miles in expanse, with fences on two sides, a wide western river as one boundary, and a wet draw as its remaining border. Along with shepherding the flock through the grazing season, seeing that my sheep partake of the natural bounty and the water sources available as conditions change, I am also tasked with keeping the herd within its defined range.

The seasonal movement of livestock with their human tenders is called transhumance, and it is practiced throughout the world.

I am one of a global population of fifty million shepherds. My kin may be bronzed Kazakhs, or black-skinned Africans, dark-haired Spaniards, brown-eyed Indians, or olive-skinned Basques, but it’s no matter — our similarities are greater than our differences. They are my people.

In southwestern Afghanistan, the Kuchi nomads move from semidesert areas in the winter into highland regions for summer grazing of their sheep and goat herds, which they raise for meat, wool, milk, and cheese. They also raise donkeys and camels for transportation, so one family may tend to four types of stock. At least one-third of all sheep and goats in Afghanistan are raised in a transhumance system, a natural process of livestock production. These nomad pastoralists keep their animals on the move, which protects local resources from overgrazing.

The Kuchi also raise livestock guardian dogs, large mastiff- or Ovcharka-type beasts that move with the herds and are treasured for their ability to kill wolves, which threaten both livestock and people. The British diplomat and adventurer Rory Stewart had one of these dogs accompany him on his walk across Afghanistan, as recounted in his fascinating 2004 book, The Places In Between.

A local man who escorted Stewart through a mountainous region of Afghanistan carried a gun on the journey. When Stewart asked why, the man explained: “Six months ago on that slope on my way to vaccinate some of the sheep on that hill, I came across the clothes and then the leg of a friend who had just been eaten by a wolf in the middle of the day. Two years ago, five wolves killed my neighbor at eleven in the morning.”

Our continued legal morass of wolf management in the United States is so incredibly far removed from other people, other cultures, who live with wolves in an intimate way. Dueling interests in America have battled their disputes out in the court systems for decades, arguing whether wolves should be managed by state or federal officials, or hunted or not, with one plan and decision seemingly leading only to another lawsuit. Little of the debate has anything to do with the reality of living with wolves on the landscape.

In the twentieth century there was an exodus of humans from Europe’s Pyrenees Mountains, and large parts of the lowlands were set aside for conservation purposes, with reintroductions and expansions of populations of a wide variety of wildlife species, including large carnivores such as bears and wolves. Much of the agricultural use of the mountain region declined, and agriculturalists remaining in the area were faced with wildlife populations that adversely impacted their livelihoods but remained fully protected. Outsiders who value conservation and ecotourism over local subsistence are in effect dictating management regimes to the detriment of the humans who live there. It doesn’t seem like a good path to follow.

Excerpted from Shepherds of Coyote Rocks: Public Lands, Private Herds and the Natural World by Cat Urbigkit, published by The Countryman Press. Copyright © 2012 by Cat Urbigkit.

Autographed copies of the book are available for purchase from the author at caturbigkit.com

Thank you.

Thanks for reading Range Writing.

Do you know someone else who should read Range Writing? This post is public so please feel free to share with a friend!