On Sunday afternoon, as Jim and I were moving a few ewes after sorting sheep, we encountered a swift fox. This carefree little canine was lounging in the afternoon sunshine at the entrance to a den along the crest of a hill.

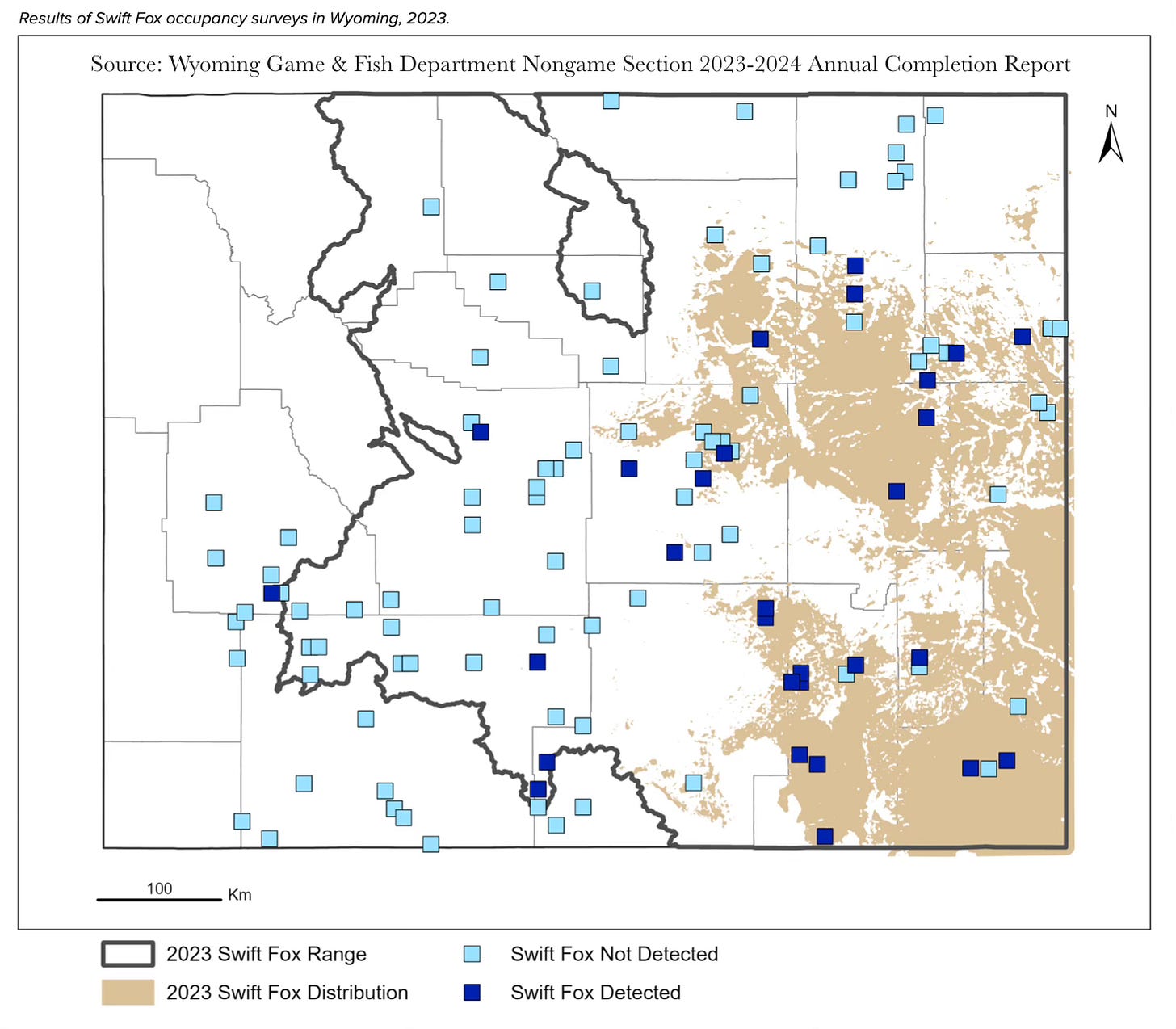

We were thrilled, as neither one of us has ever seen a swift fox. Western Wyoming isn’t part of the historic range of this species generally known as a grassland inhabitant, yet here it was in the sagebrush sea.

If we were to report the occurrence, it would be a new record for its westward range expansion. But it was on a Bureau of Land Management cattle and sheep grazing allotment. Should we add to public record, or keep quiet?

Our first concern was this: Was this a federally protected species, or a species that could be used to harm livestock management? If so, we would not report its presence. Some may say that’s greedy or petty, but others will understand our qualms about providing federal officials with reason to impose new restrictions on local livestock operations or for animal activists to use this species as a surrogate to pursue an anti-livestock agenda.

When we returned to the house, we searched for the status of the swift fox, learning that although the species was proposed for protection under the Endangered Species Act back in 1992, the listing was rejected. In Wyoming, the swift fox is a nongame species, so hunting is not allowed.

The listing question prompted more intensive searches for the animals by state wildlife agencies, but the Bureau of Land Management in Wyoming determined that the swift fox is a “sensitive species” to be considered in its land management plans. What would that mean for livestock producers? We needed to know more.

Smallest canid

We learned that this housecat-sized creature is the smallest wild canid species in the United States, that it relies heavily on den sites year-round as protection from predators, and that it mainly preys on jackrabbits, cottontails, small rodents, birds and insects. Swift foxes are often killed by coyotes and golden eagles, and coyotes represent a major challenge to their conservation.

What do they need to survive?

The most recent conservation assessment for swift fox emphasizes that grazing is necessary to maintain the health of grassland ecosystems. That’s good news: livestock grazing helps provide habitat for swift foxes. And the assessment noted that “control of coyotes may enhance the distribution and abundance of swift foxes.”

Going public

With the assumption that swift foxes shouldn’t cause harm to livestock production capabilities, and by cropping the photo so that no landmarks were included to protect its location, I decided to post a photo of the animal on my social media, in essence providing public notice of this occurrence. Why would I do that? For a couple of reasons.

First, by pointing out that the biggest natural threat to swift foxes is coyotes, I wanted to draw the link to this fox being present on domestic sheep and cattle range, where we work to deter coyotes through the use of livestock guardian dogs and we also practice targeted predator control. Our predator control program is not an eradication program but seeks to minimize damage to both livestock and the predator population.

What little I knew about swift foxes came from conversations with another sheep producer from southeastern Wyoming where he’s long lived with these small canines on his sheep ranch. Swift foxes do well in the presence of coyote control and the use of livestock guardian dogs. I want the public to understand that connection.

I only found one other recent record of swift fox in Sublette County (near the border with Sweetwater County), and I realize that this is the time of year that young swift foxes are dispersing, so this is probably a young animal.

Swift foxes are known for their curious personalities and unwary behavior, as we quickly learned in our encounter with this wild predator. Displaying a casual response to our presence, its carefree behavior makes me fear for its safety. I want this small predator to survive here, to thrive here.

Note from Cat: Your support for Range Writing is appreciated. If you aren’t already a subscriber, please consider subscribing now. It’s free, and the latest posts will be delivered straight to your inbox weekly.

Rare birds

Our sighting of a swift fox is just one of a series of encounters we’re had recently with various species that haven’t been documented here before or are viewed as rare or uncommon.

In July, a non-governmental organization released five young trumpeter swans into the Big Sandy drainage. This species is classified as a species of greatest conservation need in Wyoming but is not listed under the Endangered Species Act. We know there is good habitat available here for swans, so we were pleased a few months later when the five swans started making morning flights over the sheep pasture, spending time at a small reservoir, and visiting the river pasture. They were getting to know their new habitat. I watched for them every morning, and kept in contact with the swan researchers, letting them know when one was missing or something seemed off.

Unfortunately, it appears that a golden eagle has killed most of the swans. While the habitat is available for the swans, the behavior of this local eagle is such that the swan advocates won’t be releasing more trumpeters here again. Golden eagles are a federally protected species pursuant to the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, and the eagle is simply doing what eagles do, killing to make a living. But by targeting the trumpeter swans, it has made the release of more of these rare birds infeasible. I was saddened yesterday morning to see a lone trumpeter swan flying low over the sheep pasture.

I understand the decision by the swan advocates, knowing that a lot of time and money is invested in the captive breeding program. But as soon as I heard that a golden eagle was targeting the swans, my first thought was “welcome to the world of the domestic sheep producer.”

Golden problems

Golden eagles sometimes prey on domestic sheep, and when an eagle targets newborn lambs during the lambing season, the situation can escalate quickly. Other eagles will arrive and then a producer is faced with a congregation of eagles in their lambing pastures, which can result in catastrophic losses. Eagles that have learned to prey on lambs sometimes begin preying on adult sheep as well, and since the birds are federally protected there is little producers can do to stop them. Most of the eagle deterrence measures suggested by wildlife officials have very little effectiveness. Fortunately, due to pressure by livestock producers, there is renewed interest in exploring new options to deter eagles from preying on livestock, so perhaps we’ll have other options in the future.

We’re fortunate to have not had catastrophic losses to eagles, although we have had some losses. We’re using a combination of non-lethal deterrence measures to reduce eagle depredation and have intentionally set our lambing date to sync with the birthing season of pronghorn antelope does that share the same range. This ensures that our newborn lambs aren’t the only feast set on the table for the eagles. This works well in our situation, but each situation is different. A ranch in the eastern portion of the state has eagles that congregate in January and February and kill adult ewes faces a totally different scenario. To complicate matters, some golden eagles are full-time residents, but others migrate from Alaska to winter in Wyoming. In some areas, resident eagles may be causing the problem, but in other areas, it’s transient eagles. It’s a complex problem without an easy or clear solution.

This fall, a covey of chukars (a non-native game bird) has taken up residence in our area. They spend time in our yard most days, and our livestock guardian dogs treat them as the same as our free-ranging chickens. When Jim and I were working sheep in the pens on Saturday, the covey came by to see what we were doing, splitting up to walk around Vin, a guardian dog sleeping on the ground outside the pen, before continuing on their way to the yard.

The Others

There are other rare species that inhabit this sheep range, as good stewardship provides the conditions that makes their presence possible. That’s why I write these stories about some of these species. But there are other rare species whose presence we can’t disclose, and that’s unfortunate. We can’t allow the presence of rare species – something we should celebrate! – to be used as a cudgel against us.

Thank you.

Thanks for reading Range Writing.

Do you know someone else who should read Range Writing? This post is public so please feel free to share with a friend!

Very good story, it is unfortunate but understandable, that you can't share more.

A few years ago, i came across a Kit fox in Wamsutter while checking wells. Pretty little guy.

Good piece. I'll never forget the time when I was censusing Mexican spotted owls for the BLM, and the supervising biologist flushed an owl from a tree (in the daytime), only to have a golden eagle snatch it. The eagles also wiped out a group of fledgling peregrine falcons that were being hacked (accustomed to to independent living) on nearby national forest land. Nothing to do in either case.

I think you are wise to carefully weigh your decision. Didn' know that swift foxes were so rare in western Wyoming.